The First Confederate Monument

Many cities and towns across the South claim the Honor of having the “First” Confederate

Monument. However some of these claims fall short. It is generally acknowledged that the first organized meeting for the erection of a Confederate Monument was in October 1865 by the St. James Sunday school of the Methodist Church in Augusta, Georgia. The monument was unveiled December 13, 1873.

The first completed monument, after the war of northern aggression, is in a cemetery located on the property of Fort Gordon, Richmond County, Georgia. It is a small shaft about 10 feet high with the words “Erected in Memory of Our Boys in Gray by the Linwood Sunday School, June 1866”. Cheraw, South Carolina unveiled its monument in June 1867. Romney, Virginia’s monument has September 26, 1867 inscribed upon it. Lynchburg, Virginia unveiled their monument 1869 and at Jonesboro, Georgia there was a monument in 1869 made of cannon balls from the battlefields nearby, about 12 feet high, a circle in shape, tapering to a single ball on top. The meeting looking into the erection of the monument in Liberty, Mississippi was on Febuary 28, 1866. The monument’s cornerstone was laid November 26, 1866 and unveiled April 26, 1871. The monument at Bolivar, Tennessee was erected in 1870, but there was no unveiling or public ceremony because of reconstruction.

There is another Confederate Monument, ordered built by President Jefferson Davis in 1861, designed by Confederate Officers and funded by the Confederate Government. Construction began in September 1861 and completed in 1862. The monument stands 176 feet and is the last remnant of the only permanent structure built by the Confederate States of America. The Obelisk Chimney of the Confederate Powderworks in Augusta, Georgia, designed by Colonel George Washington Rains of North Carolina to “remain a monument to the Confederacy should the Powderworks pass away.” The Confederate Powderworks was confiscated and condemned by the Federal Government after the war of northern aggression. The city of Augusta bought the property on the condition that it tear down the old Powderworks but saved the Obelisk Chimney from destruction only after a plea from Colonel Rains. The city sold all of the property except the Chimney and 10 feet from each side of its base. On June 2, 1879 it gave custody of the Chimney to the Confederate Survivors Association of Augusta to “beautify it and protect it from injury as a Confederate Memorial.” In 1882, the C.S.A. of Augusta repaired the square castellated base, protected the corners and in the face, looking toward the canal inserted a large tablet of Italian marble, bearing, in raised letters, this inscription:

“This Obelisk Chimney- sole remnant of the extensive Powder Works here erected under the auspices of the Confederate Government- is, by the Confederate Survivors Association of Augusta, with the consent of the City Council, conserved in Honor of a Fallen Nation, and inscribed to the memory of those who died in the Southern Armies during the War Between the States”

Today this colossal cenotaph perpetuates heroic memories and reminds us of the unseen graves of the Confederacy and those who perished in its support so that future generations will know the glories of a Southern Nation and the brave deeds of those who fell in the armies of the South. The First and Oldest, the Augusta National Confederate Monument.

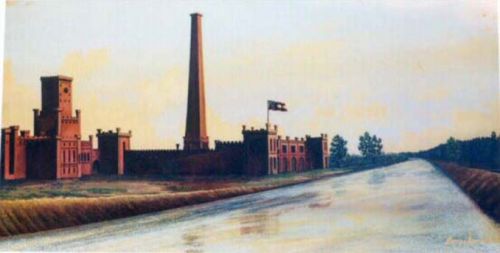

The Confederate Powder Works flying the First National Flag in 1862 overlooking the Augusta Canal.

The Powder Works and Colonel George Washington Rains

When the first Confederate shell burst over the heads of Federal soldiers holding Fort Sumter in 1861, the men that fired it were hardly prepared for war. Not an ounce of gunpowder had been made within the Confederacy in preparation for the conflict — and the amount on hand was scarcely enough to last another 30 days.

Jefferson Davis already knew that the fledgling Confederacy had no certain means of importing the supplies needed for a war no-one in the South expected. His government faced the daunting task of creating its own means of manufacturing gunpowder with sufficient speed and in great enough quantity to feed the great war machine that would be needed to keep the North at bay.

The task fell to Colonel George Washington Rains, a West Point trained engineer and artilleryman. When Rains set off on his mission on July 10, 1861, the South barely had enough gunpowder to stage one good battle. What followed was one of the technological and industrial miracles of the South — a story that has yet to receive the national recognition it deserves. Without the incredible dedication and talent of this one man, the War Between the States might well have been a minor 30 day event recorded as one of the oddities of American history. That it became instead a great conflict over Southern concepts of principle and freedom is due to the work of this one man, Colonel George W. Rains.

Within an incredible seven months, a gargantuan industrial complex covering two miles had risen above the banks of the Augusta Canal, Augusta, GA. Powered by water and steam, machinery forged in local shops under the direction of Rains began working inside specially constructed buildings. The principal product — the finest gunpowder the 19th century had ever seen. Rail lines from the centrally located Augusta carried Rain’s gunpowder to every distant part of the Confederacy. After one fierce battle with the blockade fleet, the Confederates exhausted all their powder at Fort Sumter. The Confederate Powder Works at Augusta was able to replace it with less than two days production.

The industrial marvel raised by Rains served the Confederacy until its last day. In addition to gunpowder, signal rockets, hand grenades, bronze field guns, pistols and even gun carriages and horse harnesses were shipped from Augusta under the direction of Rains.

Today, only the elegant chimney stack of the Confederate Powder Works remains as a monument to the great factory. Only a handful truly realize the importance of Augusta and Colonel George Washington Rains to the greatest conflict ever known on American soil.

Leave a Reply