http://www.jewish-history.com/civilwar/moses_ezekiel.html

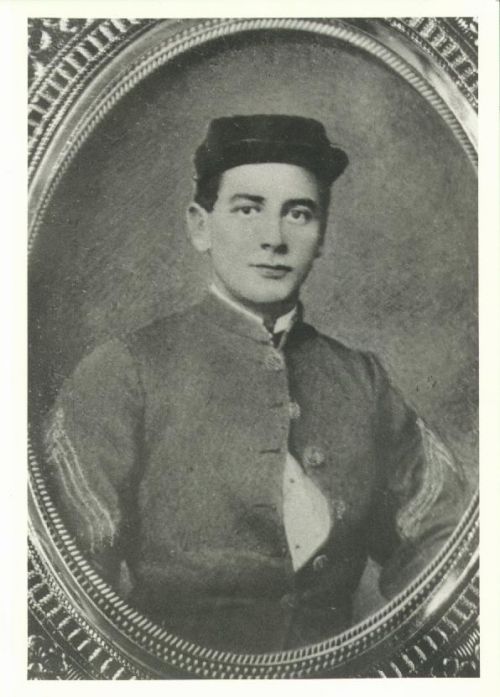

Moses Jacob Ezekiel*:

From Confederate Cadet to

World-Famous Artist

* Ezekiel is often referred to in America incorrectly as “Sir Moses” in reference to his Italian and German honors; he could more correctly (albeit awkwardly) be referred to as either “Cavaliere” Ezekiel or “Herr von” Ezekiel.

Contributed by by Albert Z. Conner

From the humblest origins, Moses Jacob Ezekiel sought a public education at America’s first state military college, the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) during the Civil War. While at VMI, he fought as a member of the VMI Cadet Battalion on the Confederate side at the Battle of Newmarket (May 15, 1864). There he witnessed the deaths and maimings of some of his closest friends. He remained with the cadet corps and fought in the Richmond trenches in defense of his native city. After the war, Ezekiel returned to VMI and graduated in 1866. He then launched a brilliantly successful artistic career in Europe where, despite a long life as an émigré, he remained close to his American and Virginian roots.

One of 14 children, Ezekiel was born on October 28, 1844 in Richmond, Virginia, in a now-demolished house on “Old Market Street,” on the west side of 17th Street between Main and Franklin, in a poverty-stricken neighborhood. The family also lived in a house (demolished in the 1930’s) on the southeast corner of Marshall and 12th. His grandparents, of Spanish-Jewish origin, had immigrated in 1808 to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from Holland—where the family had fled some 400 years earlier following the Spanish Inquisition.

By the beginning of the American Civil War, Ezekiel had quit school and was engaged in the mercantile business when he decided to go to college. VMI, as a public college and then under a wartime regime, was one of the few institutions available to him at reasonable cost and considering his relatively poor academic preparation. His mother, Catherine de Castro Ezekiel, appreciated that the wartime situation might lead him to fight for the South. She admonished him, as she sent him off to VMI to learn the arts of war, that she wouldn’t have a son who would not fight for his home and country.

Considering the well-documented anti-Semitic prejudice pervasive in Richmond and America at that time, his mother’s was a courageous and benevolent attitude (which her son seemed to share). A contemporary description of Civil War Richmond (pointing out that the Northern states were equally so disposed) in H.M. Sachar’s A History of the Jews in America (1992) — which amazingly doesn’t mention Ezekiel in its Civil War section— demonstrates something of that poisoned atmosphere:

“One has but to walk through the streets and stores of Richmond, to get an impression of the vast number of unkempt Israelites in our marts—Every auction room is packed with greasy Jews—Let one observe the number of wheezing Jewish matrons—elbowing out of their way soldiers’ families and the more respectable people in the community.” [attributed by Sachar to the Richmond Examiner]

Ezekiel entered VMI on September 17, 1862 with the Class of 1866, which originally contained 147 members. His class included the son of a Virginia governor, and sons of the professional and landed classes of the state. It also included, due to need-based scholarships known as state cadetships, the sons of Virginia’s poor. He ultimately graduated last among 10 graduates (all members of the Newmarket Corps) on July 4, 1844 (45 of his class—including 36 fellow members of the Newmarket Corps—were later declared “war graduates” and thus ranked behind him).

Ezekiel later explained his reasons for going to VMI and, by implication, fighting for the Confederacy. He asserted that he’d gone there, not to defend slavery—an institution which, in this thinking, had unfortunately been inherited and limited by Virginia. Rather, Ezekiel further asserted, he went there to defend Virginia when she seceded to avoid providing troops to the Union to “subjugate her sister Southern states”. These views were typical of the VMI cadets of that period, ignoring the fact that his state in 1868 had the largest slave population in the South and, over the previous 30 years, had exported 200,000 slaves to the other Southern states.

His cadet career, however, was neither typical nor easy. Ezekiel commenced his cadet career by refusing to take the physical abuse routinely meted out by an old cadet he encountered, and by several others who “visited” him that night. His grandfather and namesake, Moses A. Waterman’s correspondence related that he’d initially believed Ezekiel wouldn’t be able to come to VMI at all because of “war conditions.”

As VMI’s first Jewish cadet there were some unusual letters; for example, in March 1863, Superintendent Major General F.H. Smith had to gain Board of Visitor’s permission for Moses to be furloughed to join his family for the “Feast of Unleavened Bread.” As Moses was apparently the first of his family to go into a military school, some reorientation at home was also necessary: his grandfather had wanted him excused from VMI summer camp in 1863 for fear of “disease” he might contract from exposure.

His artistic talent also left a lasting impression. A 1940 letter to VMI from a lady in Shawsville, Virginia, revealed that his artistic talent had become evident early in his cadetship. She related that Ezekiel, while visiting Shawsville with fellow cadets J.K. Langhorne [VMI 1866] and M.D. Langhorne [VMI 1867], had sketched their sister on horseback while she waited at the train station. Miss Lizzie Langhorne, apparently never knew she was a subject of the young cadet’s drawing (she herself, however, later married Mr. J.M. Payne of Amherst, Virginia, and became the grandmother of a VMI cadet, N.P. Gatling [VMI 1922]).

One of the lasting memories of the Class of 1866 was the May 1863 death and funeral of Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, who had spent the last 12 years of his life on VMI’s faculty. Ezekiel was one of the corporals of the guard—who had the primary mission of ensuring that overzealous cadets didn’t pluck too many floral souvenirs from “Stonewall’s” heavily bedecked metal casket as it lay in state in his old VMI classroom—before Jackson’s burial.

Young Moses apparently didn’t cut an imposing figure as a soldier. Years later, in 1903, classmate John S. Wise [VMI 1866], provided a colorful tongue-in-cheek description of Ezekiel as a cadet:

“…he never could chisel himself into a pretty soldier. His head was as large as a Brownie’s, his body thickset, and his legs were very short. In fact, he looked like a tin soldier that had been broken in the middle and mended with sealing wax. I resented bitterly the fact that of all the Sergeants he was the only one I ranked.”

Regardless of his lack of parade ground prowess, Ezekiel’s war service came as a member of the Newmarket Corps or “Baby Corps,” which fought effectively as the 295-man VMI Cadet Battalion in the Newmarket Battle. Moses Ezekiel participated in the fight as a private of Company “C,” first in the forced march to Staunton, Harrisonburg and Newmarket, and then in the direct assault on the Union positions which defeated Sigel’s forces. The battle was credited with saving the Shenandoah harvest for the Rebel forces fighting in the East.

After the battle, Ezekiel’s efforts focused on the sad mission of recovering the dead and wounded )the small cadet battalion had suffered 24 percent casualties). He first wandered the battlefield with B.A. Colonna [VMI 1864] searching for their mutual friend, Thomas Garland Jefferson [VMI 1867], a descendant of the third U.S. President. They found Jefferson, desperately wounded in the chest and lying in a hut. Ezekiel then walked, fare-footed (as his shoes had been lost in the mud during the assault), into Newmarket to find a wagon.

The subsequently took Jefferson to the home of Lydie Clinedinst (Ezekiel wrote in 1884 from Rome to clarify misinformation that Miss Clinedinst (Mrs. Crim) had been confused with another lady or ladies, and had done no more than provide her home to the cadets). While Jefferson remained in bed in agonizing pain for two days, Ezekiel nursed him and read to him from the Bible.

On the evening of Tuesday, May 17, 1864, by candlelight, the Clinedinst family listened as young Moses read to his dying Christian friend the requested passages from the New Testament (John, Chap. 14): “In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you.” As Jefferson’s fevered mind wandered, he thought Ezekiel was first his mother, and then his sister. As he lost his sight, he asked for a light. “Only then it dawned on me,” wrote Ezekiel, “that all hope was past and [he was] in his [death] agony.” The family gathered around, as Ezekiel held him in his arms while he died.

Ezekiel was promoted to cadet orderly or first sergeant of Company “C” after Newmarket. He completed his educated—interrupted somewhat by the burning of the Institute, its relocation to the Richmond Almshouse, the Richmond-Petersburg Siege, disbanding the cadets corps, and the final surrender.

In his final year, he came to the attention of Robert E. Lee, newly resident in Lexington as the president of Washington College, and Lee’s wife. Lee encouraged him to pursue his artistic talents:

“I hope you will be an artist, as it seems to me you are cut out for one. But, whatever you do, try to prove to the world that if we did not succeed in our struggle, we are worthy of success, and do earn a reputation in whatever profession you undertake.”

Lee’s talk inspired Ezekiel and he exceeded the old man’s charge. He turned out some fine paintings, among them “Prisoner’s Wife,” which he gave to Mrs. Lee. His first sculpture was a bust of his father. He also did an ideal bust “Cain, or the Offering Rejected.” Ezekiel then spend a year at the Medical College of Virginia studying human anatomy, before he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to study at the Art School of J. Insco Williams and in the studio of T.D. Jones—where he completed a statuette entitled “Industry”.

With little point in returning home to Richmond, where his parents had lost everything and opportunities were non-existent, Ezekiel followed the advice of Cincinnati artists and went abroad to Berlin. In the German capital, he studied at the Royal Art Academy. There he earned money by teaching English and selling some of his works.

At the age of 29, he won the Michel-Beer Prix de Rome—the first non-German to do so—with a bas relief entitled “Israel.” The prize allowed him to go to Rome, which he made his residence for the rest of his life. He was subsequently knighted by King Victor Emmanuel of Italy and decorated by King Humberto. His other awards included the “Crosses for Merit and Art” from the Emperor of Germany; another from the Grand Duke of Saxe-Meiningen; and the awards of “Chevalier” and “Officer of the Crown of Italy” (1910) from the King of Italy. Ezekiel also received the Gold Medal of the Royal Society of Palermo, Italy; the Silver Medal at the St. Louis Universal Exposition (1904); the Raphael Medal from the Art Society of Urbino, Italy.

His sculptures were in the romantic, elaborate and ornate style which was highly popular in the Victorian era. Ezekiel accomplished some 200 works in his prolific career. Among his greatest was a marble group, “Religious Liberty,” or “Religious Freedom,” created for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, the work arrived too late for the exposition; but, it was nevertheless displayed in Fairmont Park from 1876 until it was moved in August 1985 to the grounds of the National Museum of American Jewish History at 55 North Fifth Street, within sight of Independence Mall. It was rededicated on May 14, 1986.

Among his most important works were: “The Martyr” or “Christ Bound for the Cross;” “Christ in the Tomb;” “Homer Reciting the Iliad,” and the University of Virginia; “Eve Hearing the Voice;” “The Fountain of Neptune;” “Pan and Amor;” “David Returning from Victory;” “David Singing His Song of Glory;” “Judith Slaying Holofornes;” “Jessica;” “Portia;” “Demostene;” “Sophocles;” and 11 decorative portrait statues in the Old Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington, DC. He also did a huge Columbus statue for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

A number of Ezekiel’s works were directly related to his ties to Virginia, VMI and the South. He did an allegorical statue o Thomas Jefferson for Louisville, Kentucky, and a replica for the University of Virginia. He accomplished a “Stonewall” Jackson statue for Charleston, West Virginia, and a replica which replaced Ezekiel’s own “Virginia Mourning Her Dead” in 1912 in front of VMI’s Jackson Arch. Ezekiel explained that he had conceived it about a decade earlier as a memorial to his fallen cadet comrades. Seeing the fresh young cadet faces before him at the dedication, Ezekiel recalled “Something arose like a stone in my throat, and fell to my heart, slashing tears to my eyes.”

A less well-known, Civil War-related work, a bronze entitled “The Outlook,” depicts a Confederate soldier (accomplished in 1910) looking our at Lake Erie from the Confederate cemetery at the site of the former prisoner-of-war camp at Johnson’s Island, Ohio—where many of his fellow VMI men had been imprisoned and several were buried. In 1910 he made what appears to have been a final visit to the U.S. where he was a guest at the VMI commencement. His last work (1917) was a bronze statue of a fellow Richmond resident and artist, Edgar Allen Poe, later in Baltimore’s Wyman Park.

When World War I trapped Ezekiel in Rome, he put aside his sculptures to help organize the American-Italian Red Cross. Shortly afterward however, on March 27, 1917, he died in Rome, where he had maintained his studio in the Baths of Diocletian. Because of the was—ironically the U.S. Joint Resolution to declare was was written by his fellow Newmarket Corps cadet, Senator Thomas Staples Martin [VMI 1867]—Ezekiel’s body was temporarily interred in the family crypt of Adolpho De Bosis.

In life, Ezekiel had been honored by several Italian Kings, Robert E. Lee, U.S. Presidents Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson, and such notables as Mark Twain, Thomas Nelson Page, J.P. Morgan, Anthony Drexel, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Franz Liszt, and Kaiser Wilhelm II.

With his passing, a New York Times dispatch from Rome reported:

“The death of Moses Ezekiel, the distinguished and greatly beloved American sculptor, who lived in Rome for more than forty years, caused universal regret here.”

Late in life, however, his heart had sentimentally returned to his Virginia roots and to “The VMI, where every stone and blade of grass is dear to me, and the name of the cadet of the VMI, the proudest and most honored title I can ever possess.” His body was shipped aboard the Duca degli Abruzzi from Naples, Italy, on February 27, 1921.

True to his loyal words, in a March 31, 1921, burial ceremony—the first held in the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, and presided over by U.S. Secretary of War John W. Weeks, Ezekiel was laid to rest next to his Confederate memorial. Flanking his flower-bedecked and American-flag covered casket, were six VMI cadet captains and two other cadets, including future Marine Commandant Randolph McC. Pate [VMI 1921]. At the gravesite, a small headstone was placed. Its simple words spoke volumes:

Moses J. Ezekiel

Sergeant of Company C

Battalion of Cadets of the

Virginia Military Institute

During the funeral the Marine Band played Liszt’s “Love’s Dream”‘ a message was read from President Warren G. Harding, who praised Ezekiel as “a great Virginian, a great artist, a great American, and a great citizen of world fame;” a tribute was paid by Rabbi D. Philipson of Cincinnati (who wrote a monograph on Ezekiel the following year); and a Masonic interment was conducted by the Washington Centennial Lodge No. 14, F.A.A.M. A separate ceremony was conducted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy at the Scottish Rite Temple.

In the subsequent years, except in Virginia and in academic circles, Ezekiel’s memory sadly faded. Appropriately, his biography was included, along with those of the other 294 members of the Newmarket Corps, in a 1933 work by William Couper. Ezekiel’s 1912 typescript manuscript memoirs (which formed the basis for a 1974 book, Moses Jacob Ezekiel: Memoirs from the Baths of Diocletian, edited by J. Gumann and S.F. Chyet; Wayne State Univ. Press), is in the VMI Archives. Earlier works on Ezekiel are: American Art and American Art Collections, Volume II (Boston, 1889); American Jewish Yearbook, Volume 19, 1917/1918; Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 60, No. 2, April 1952.

A major exhibit of Ezekiel’s works and life was conducted in 1985 by the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia and Richmond, and in Grand Rapids, Iowa. An exhibit is also housed in the Beth Ahabah Museum, Richmond, Ezekiel’s home synagogue. Ezekiel papers and letters are in the Museum of the Confederacy. Of the nearly 2000 VMI alumni, faculty members and members of the state-appointed governing Board of Visitors, Ezekiel’s VMI alumnus file is one of the largest in the VMI Archives.

New Market Cross of Honor Awarded to Ezekiel and the other members of the

VMI Cadet Battalion

Virginia Military Institute

Ezekiel’s statue of

“Stonewall” Jackson,

uttering his famous words, “The Institute will be heard

from today,” at the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 2, 1864. Jackson Arch of the VMI

barracks is in the background

photo by

Marshall A. Conner

Ezekiel’s statue of

“Virginia Morning Her Dead” honoring the VMI Cadet Battalion at the Battle of Newmarket,

May 15, 1864. Six of the cadets killed in the battle are buried behind the monument.

photo by

Marshall A. Conner

From Albert Z. Conner, Bayonets, Butternuts, and Bowlegs: VMI’s Civil War Soldiers, work in progress.

Leave a Reply